C. What is Public Health Ethics?

Defining Public Health Ethics

Before moving deeper into this module, let's first establish what Public Health Ethics is.

It is mostly about what should and shouldn’t be done ... collectively… to protect and promote the health and health equity of communities.

Public Health Ethics

Public Health Ethics is mostly about what should and shouldn't be done, collectively, to protect and promote the health and health equity of communities.

The highlighted elements in this definition (should, shouldn't, collectively, health and health equity and communities) are particularly important. “Should” or “ought” signify that it is a normative exercise (i.e., it is about what is appropriate or best to do, and not just a description of what people actually do). “Collectively”, denotes public health as an organized societal effort undertaken on behalf of everyone, and “communities”, highlights that interventions and their effects are considered at a community-wide or population level.

It is very important to notice both “health” and “health equity.” This makes it explicit that public health has two primary moral aims: one is concerned with protecting and promoting the health of the entire population, and the other involves reducing the unfair distribution of health burdens and risks that affect “adversely historically situated social groups” (Faden and Powers, 2008, p. 153). Thus, public health ethics is also about power and about everyone having fair access to resources.

Situating Public Health Ethics in the Broader Theoretical Context

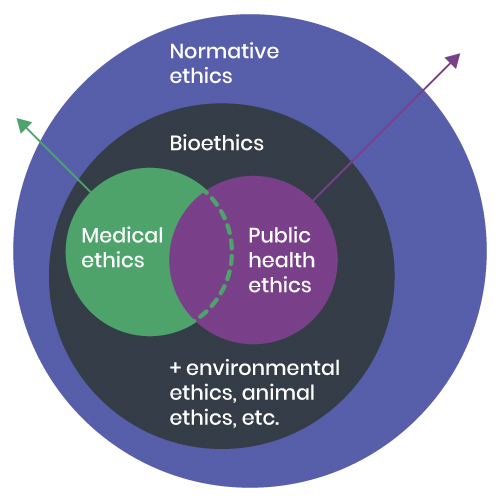

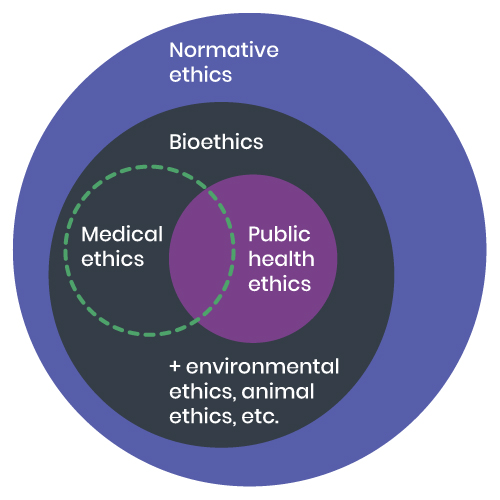

Public health ethics, represented by the blue circle in the figure below, can be situated within normative ethics. It is also situated within the field of bioethics, alongside medical or clinical ethics, environmental ethics, and animal ethics. We often see bioethics and medical ethics being treated as identical. This is because medical ethics has received so much of the attention within bioethics. Angus Dawson is a leading public health ethicist. He points out that bioethics is a larger field that covers, as the name suggests, the ethics of living things or the ethics of life (Dawson, 2010a). Bioethics can be seen to include medical ethics and public health ethics, and while they have a lot in common, they are distinct in certain ways.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

How do Public Health Ethics Differ from Medical/Clinical Ethics?

Medical interventions are quite different from those typically found in a public health context. For example, medical interventions tend to focus on individuals. Normally, they involve a patient going to see a practitioner and seeking some kind of intervention in a clinical setting, and where the patient is in theory free to accept or reject the therapy that is proposed by the practitioner as being in the best interest of the patient.

- Focus on individuals

- Patient seeks out clinician

- Cure

- Clinical settings

- Patient amy reject advice

- Should be in the interest of patient

- Focus on populations

- Public Health practitionaler seeks out 'patients'

- Prevention

- Community settings

- Can be hard to opt out

- May not be in the best interest of some individuals

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Interventions in public health have as their purpose the promotion and protection of the health of populations as well as reducing inequitable disparities in health. One could say that it is the public health practitioner who approaches people (that is, the public) to prevent disease or to improve health in a community context. It is sometimes difficult for individuals to avoid or opt out of public health interventions (for example, water fluoridation, indoor smoking bans, etc.), and even if some interventions are good for the health of the population as a whole, they may not be entirely in all of the interests of some individuals, including some interests beyond public health. In medical contexts, both the benefits and harms being considered tend to accrue to the individual patient, whereas in a population context, some groups may benefit while other groups are harmed by an intervention.

It is worth noting here the important focus on equity and social justice in public health ethics. It emerges in at least two ways. First, the population-level focus of public health means that differences between sub-populations are studied. Also, public health is focused on health outcomes across populations but also on the various causes of those outcomes, including the social determinants of health that lead to non-random disparities in health among populations. Action for health equity means addressing the causes of the disparities in power and access to the opportunities and resources that produce health in order to reduce those gaps.

These differences between medical and public health practices are also reflected in their respective ethics. This is the main reason why public health has come to have its own distinct ethics. Many people associate Beauchamp and Childress’ four principles approach with medical ethics. Their Principles of Biomedical Ethics (Beauchamp & Childress, 1994), focusing on respect for autonomy, justice, beneficence and non-maleficence has, for better or worse, been the dominant approach in medical ethics since it was published in 1979. Since about 2000, public health has been developing its own unique approach to ethics to better reflect public health practice.

Ethics Applications for Everyday Public Health Dilemmas

Most situations in public health are a lot more common and ordinary than the Ebola case we started with. In that case, decisions were to be made in an emergency situation, the consequences for people were dramatic and immediate, and they involved scarce resources and could result in tragic effects. However, public health policies include interventions that affect everyday life, such as:

- water fluoridation

- iodide in salt

- higher minimum wages and income support programs

- smoking restrictions

- traffic-calming policies

- advocacy for affordable housing

- nutrition labelling

- taxes on sugary drinks

- confronting racism, sexism and other forms of unjust discrimination

- vaccinations (e.g., HPV)

- workplace health and safety regulations

just to name a few. Some are more controversial, some are less so. Public health ethics applies to these as well, not just to the kind of emergency that we describe in our ‘typical’ case. Decisions made around these interventions have important health effects on the population.

While we are on the topic, it is worth noting how important healthy public policies are to this list of interventions. Healthy public policies are government policies that lie beyond the purview of the health care system in sectors as diverse as transportation, taxation, occupational health, education, housing, agriculture, etc., among others. Even though they may not be health policies per se, these policies nonetheless have significant impacts upon health of the population and groups within that population.

Ethical domain

Apply what you have learned about the distinctions between normative ethics, bioethics, clinical or medical ethics, and public health ethics to identify the ethical domain most closely represented by each of the following examples.